BioMate

Lab-bench biologists find it difficult to use many existing tools for their data analysis. These tools are generally command-line computer programs written by computational biologists. Computational biologists do not have time to create user-friendly interfaces for their programs, and often find themselves spending a lot of time helping lab-bench biologists run their programs. This creates a burden for all involved: lab-bench biologists cannot move forward with their data analysis, and computational biologists cannot move forward with their research.

{html}<MCE:STYLE></MCE:STYLE><MCE:STYLE mce_bogus="1"></MCE:STYLE><STYLE mce_bogus="1"><!--

.pagetree2 a{font-size:16px; }

--></STYLE>{html} |

Click on a page above for a specific section.

Design

Our final design focused on simplicity and learnability for lab-bench biologists and learnability and efficiency for computational biologists. One major design decision was whether to make two separate interfaces for the two user groups or to make a common interface for both. We decided to design a common interface because, the roles of our two user groups are not totally isolated and overlap in a number of tasks. We tried to make the most common task of a lab-bench biologist which is generating the command for using a script, simple, intuitive and learnable. On the other hand, we tried to design the task of creating or editing a script to be as efficient as possible since the computational biologists are efficient users of computers. We incorporated support for both keyboard and mouse actions throughout our interface (e.g. tabbing through fields, click vs enter etc.).

|

On the login page, we wanted to make the actions “Sign in” and “Create an account” more visible, so we used big blue buttons for them. We tried to make the placement of these buttons externally consistent with popular web applications like gmail. |

|

The design of our landing page went through a number of revisions. The design considerations were - what actions to put in the action wheel, how the actions should be placed, how to remove ambiguity from the names of the actions, whether the labels of the actions should be hidden or displayed, what icons to use etc.

- We decided to put the four actions in the action wheel which we found to be the most important ones based on our needfinding and user feedback from paper prototype test.

- We placed the actions on a circular action wheel to get the advantage of proximity by Fitt’s law.

- We followed the principle of “less is more” while choosing icons for actions.

- We changed the name of the action “Run Script” to “Use a Script” because during paper prototype tests some users felt they would only click on a button labeled "Run Script" if the script had already been loaded. They also were confused about clicking on "Run Script" if they just wanted to access their previously saved settings for a script, and not necessarily run it.

- We made the action buttons big and clearly labeled them so that users can get a sense of the purpose of each action right away just by looking at it.

- We also made the “Sign out” button red with a commonly used icon and placed it at the top right corner so that, it is more visible to the users.

|

|

- In our initial design we put only home and sign out buttons at the top navigation bar, so the user was forced to go back to home page if he wanted to perform a different action. Later we decided to include “Use a Script” and “Create/Edit a Script” actions on the top navigation bar since a computational biologist user might want to switch between them frequently. However, we did not include “Notes” and “History” because notes associated with a particular script is available on the script’s page and history is also available in the form of saved parameters.

- The script names in the “select script” dropdown list appear in alphabetical order. We also decided to display the name of the author of a script if it was shared by someone else so that no ambiguity arises when scripts with same names but different authors exist.

|

|

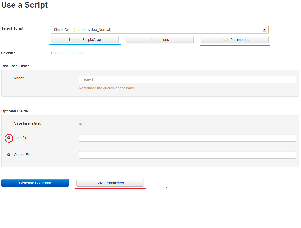

- The primary goal of a user on the page of particular script is to generate the command for using the script. So we made the “Generate Command” button big and blue.

- The notes associated with a script is available on click on the notes button which is placed right under the name of the selected script, so that user doesn’t miss it. Also the history of runs for this particular script that the user saved is readily available on click on the “Load Parameters” button.

- If there is a tooltip available for a particular field, a “?” icon is shown at the left of the label of that field. This setting of tooltips is quite common in web applications.

- Warnings about different fields are shown just below the textbox associated with it. We use proximity of placement of warnings to textboxes and increased whitespace among two textboxes to give the user a sense of which warning is associated with which textbox.

|

|

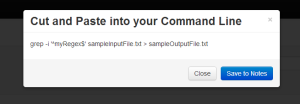

When user presses the “Generate Command” button, an overlay is shown with the generated command. The user can save the generated command to his notes by hitting the “Save to Notes” button. |

|

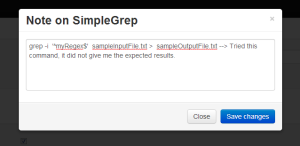

Note for a particular script is displayed in an editable textbox as an overlay. The user can edit inline and save right away. |

|

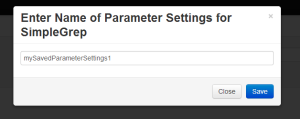

Clicking on “Save Parameters” asks the user to provide a name for the configuration so that, he can load this configuration later. An alternative design may have been akin to how ms word works, in which a user would view all their save files for the script in

one place. Such an implementation would have allowed users to name their parameter settings while keeping the previous names in mind, thereby allowing them to develop naming conventions. However, we did not have time for this more complicated implementation. |

|

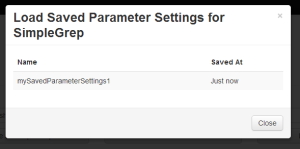

Clickng "Load Parameters" allowed the user to select a previously saved parameter configuration. Note that saves within the last minute are displayed with the words "Just now", which we felt was more informative than just listing the time. |

|

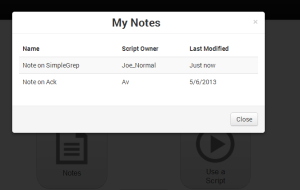

On the homepage, clicking on “My Notes” shows the user an overlay with a scrollable list with all his notes. Recently accessed notes appear on the top of the list. We also show the names of the script owners so that no ambiguity arises when two different owners have scripts with same name. The choice of overlay seemed more appropriate because it avoids unnecessary page switching. |

|

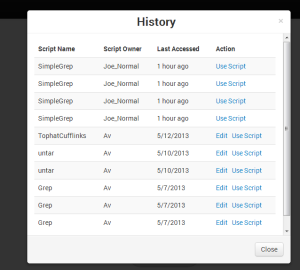

Clicking on the “History” button on the homepage shows the user an overlay with a scrollable list of his ten most recently accessed scripts. If the user is also the owner of the script, then both “Edit” and “Use Script” options for that script is available in the list. The choice of overlay seemed more appropriate because it avoids unnecessary page switching.

As designed, the 'history' is populated only when a user pressed 'generate command', but the parameter settings that were used to generate the command are not saved. In retrospect, this would have been a good feature to implement, so we might consider incorporating it in the future. |

|

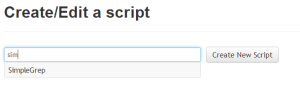

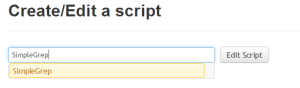

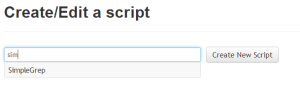

If the user selects Create/Edit Script on the home page, they are presented with this screen. We made the create/edit script button do substantial double duty. It is greyed out if the text box is blank. If the user enters a new script name or selects a prexisting script, the button changes accordingly. |

|

The list of scripts works like autocomplete. If the text in the textbox does not correspond to the name of a prexisting script, the button changes to "Create New Script". |

|

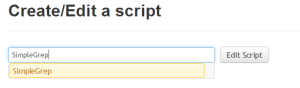

If the name of the script in the textbox corresponds to an existing script, the button changes to "Edit Script" |

|

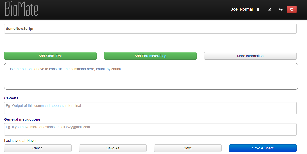

When a new script is created, the user is taken to this landing page. We made the design decision to force a user to name the script prior to creating the script - as opposed to programs like Microsoft Word which allow you to create untitled documents and only require you to specify a name while saving. We made this design decision as it allowed us to couple loading an old script with creating a new script up front. However, the violation of external consistency did cause confusion. |

|

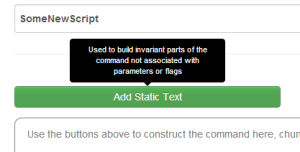

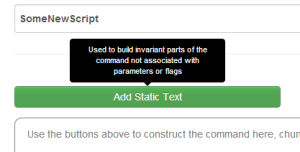

Commands are constructed as chunks of 'static text' (not associated with user input) and parameters/flags (associated with user input). Tooltips are provided to explain what each of the buttons do. |

|

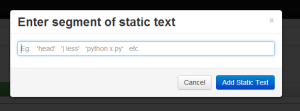

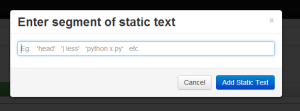

Pressing 'Add Static Text' introduces this overlay, with the focus on the input field. |

|

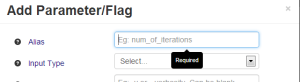

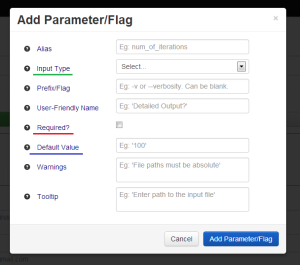

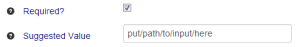

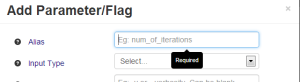

Pressing 'Add Parameter' introduces this overlay, where the user fills in details about the parameter. Parts of this overlay change dynamically depending on what the user selects. To facilitate fast entry of similar parameters, the values of 'Input Field' and 'Required' are remembered when the user tries to create a new parameter, while other fields are cleared. |

|

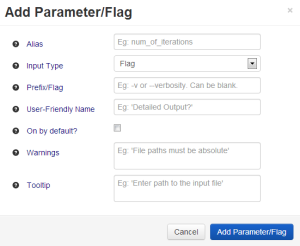

For instance, if the user sets 'Input Type' (green underline above) to Flag, the 'Required' checkbox (red underline above) disappears (as it does not make sense to 'require' a flag, which by definition can be either on or off), and the 'Default Value' line and associated input text field (underlined in blue above) turn into 'On by default?' and a checkbox respectively. |

|

Making a parameter required changes the 'Default Value' label to 'Suggested Value', as it does not make sense to have a default if the user is required to provide input anyway. In the lab-bench biologist facing side of the interface, 'Default Values' are filled in with pending delete, while 'Suggested Values' are filled in as placeholders. |

|

If the user leaves critical fields blank and tries to press 'Add Parameter', the interface will complain by returning the focus to the field that has an error and providing a tooltip. Feedback we received indicates that this error calling could be made more conspicuous, perhaps by highlighting the problematic checkbox in red. |

|

When parameters are added, the details of the parameter appear in a table. Parameters can be edited from the table. We decided to include this table in addition to the window where chunks of the command can be dragged around after feedback we received on our paper sketches. |

|

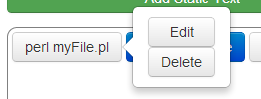

There is redundancy in how the user can edit command chunks: they can edit from the table, as mentioned before, or they can click on a chunk and press 'Edit'. This will bring up a popup where the user can make changes. |

|

To save a script, the user presses the save button. The script is saved under the name specified at the time of creating the script (note: this differs from the style of programs like MS Word, as discussed previously). Feedback appears as an updated time in green, but during user testing we discovered that this feedback could be louder. |

|

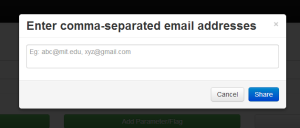

To share the script with the public, the user presses 'saveNshare'. This brings up an overlay where the user can enter the email addresses of the people they want to share the script with. Script sharing works by appending the script ID to the BioMate URL; anyone with the link can access the script. This allows a user to share a script with a mailing list without any problems. |

|

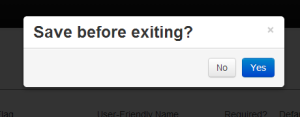

If the user presses cancel to exit the page, they are presented with a confirmation box to ensure they don't accidentally leave behind unsaved work. |

Implementation

Front End

We implemented the front end of our interface using Javascript and HTML/CSS. We relied heavily on two external libraries: Twitter Bootstrap and JQuery. In particular, we used Bootstrap features such as modal popups and tooltips, as well as built-in Bootstrap layout and styles in order to keep our interface consistent throughout all screens.

Back End

The back end of our interface was implemented using Parse. We decided to use Parse since we would not need to write any server-side code or maintain a database server – Parse handles all server-side code. Parse also has several very useful features including a built-in User class for managing user accounts, password reset, and everything associated with a secure user session. Parse also has a feature for dynamically sending emails to user-specified email addresses, which we found useful for implementing sharing scripts.

As mentioned above, we used the built-in Parse.User class to manage user sessions and secure login. In addition, we created a set of Parse classes in order to encapsulate interaction with the back end and separate it from our UI elements. The major classes we created were:

- Script: This is the main class holding all script data including the name, owner, and list of parameters and static text comprising the command

- UserScript: This class is used to implement sharing scripts. Whenever a script is shared with a particular user, an instance of UserScript is created.

- History: This class stores the script access history for each user. Whenever a user creates/edits a script or uses the script to generate a command, we add an instance of this class.

- Note: This class stores user-created notes on particular scripts.

- SavedScriptParams: This class stores the set of parameter values a user has saved for a particular run of a script.

Each class has instance-level methods to edit or delete a particular instance of the class, as well as class-level methods to create a new instance or select a set of objects matching certain criteria.

We implemented automated email sharing of scripts using Mailgun-Parse Cloud, which is another feature available through Parse. When the owner of a script decides to share it with others, they specify a set of email addresses, and a link containing the script id is automatically sent to those addresses. Any user with the link can then log into BioMate and access the script. We decided to add a “UserScript” instance at the point when the user logs in (rather than at the point the owner clicks "Share") to facilitate sharing, since the script owner may want to share the script with a panlist or with someone who does not yet have a BioMate account. Additionally, we have found that existing applications such as Google Docs already use this paradigm, and external consistency is a desirable feature.

Evaluation

We performed our user test by briefing each user with a scenario and asking them to perform certain tasks using our interface. We found our users in a biology lab at MIT that collaborates heavily with computational biologists, which we expect to be our target user population. In total we tested two lab-bench biologists from this lab, as well as one computational biologist also affiliated with the lab. Below is the briefing we gave our users:

Scenario for the lab bench biologist

Av has made a graphical interface on BioMate for you that will allow you to use the tophat/cufflinks script more easily (this is a script that members of the lab are already familiar with). The interface will allow you to specify what your inputs and options are, and then press a button to generate the correct command-line syntax for the tophat/cufflinks script, which you can then cut and paste into the terminal.

Tasks

- Open your email and access the link from BioMate.

- Find your way to the interface that Av made for you.

- Generate a command for tophat/cufflinks. For the purpose of this user test, imagine you have an input file already on the server (stored in whatever location you like and named whatever you like). You want the job to execute relatively quickly, so use 7 processors instead of the default 4.

- Imagine you cut and paste the command into the terminal, and the job is running. You would like to record the command you just launched for future reference. Make a note to document the command you launched and the date.

- You would like to come back to this later. Save your parameter settings and log out.

- A new day! Log back in and access the script again. This time, access it via your history.

Scenario for the the computational biologist

There is a utility called intersectBed on the server that can be used to intersect two files in the bed format. Command-line help for this command can be obtained by logging into the server and typing 'intersectBed'. A lab bench biologist would like to intersect two bed files on the server. Your task is to use BioMate to create an interface that will allow the lab bench biologist to specify the input files and the options. The lab bench biologist will then press a button labeled "generate command" to generate the correct command line syntax for the job they want to run.

Tasks

- Create an account on BioMate and log in

- Make a new interface for the intersectBed command. As a reminder, the syntax for intersectBed is:

intersectBed [options] -a file1 -b file2

You should support the following options (you can read about the options by typing intersectBed into the terminal):

-u

-wa

-wb

optionally writing the results (which by default appear in the terminal) to an output file. Because intersectBed does not support writing to an output file, you will have to do this using "> [name of output file]".

- Inform the user that if one file is much bigger than the other, then the smaller file should be -b so as to optimize the running. Also warn the user not to have a very big file for -b as it would crash the server.

- Save your creation

- Find a way to view the script as it would appear to the lab bench biologist. Make any changes as you desire, then share the script with mars_ui_team@mit.edu.

Notes from Lab-Bench Biologist 1

- At first he thought his account had already been created, but then he figured out that he needed to go to “Create account”.

- Log-in didn't seem to work. He clicked on “Can't access account” and got an error saying the account didn't exist.

- He created another account with a different email address, which worked. (Perhaps there was an issue connecting with Parse the first time)

- He easily navigated to the "Use a Script" page to use the Tophat/Cufflinks script, as described in the briefing.

- The first thing he did was view the "Instructions". He said they took him a little while to understand and could be more informative.

- Then he clicked on "Load Parameters", and saw that the popup was blank.

- He looked over every tooltip first, and said they were generally unhelpful. Additionally, one of the tooltips overflowed because of a very long path name.

- He was not sure whether our interface would directly connect to the server to run the script, or just generate the command.

- He also misunderstood the input file parameter and thought we wanted him to create an input file. We told him to just pretend he already had a path to an input file he wanted to run.

- In order to find a sample file path, he ssh’d into the server and used “cd” to find the path to some input file.

- He figured out what the notes and saving parameters were for, and said they seemed useful.

- We asked him to take a look at his History from the home page. He said he found it a little confusing that the author was listed as Av, but it seemed useful.

- Some of his confusions were related to the fact that this was a test and the input/output files didn’t actually exist.

- Overall, he liked the interface and was excited to use it in the future.

Notes from Lab-Bench Biologist 2

- The email link took a little while to show up.

- She asked whether she already had an account

- She saw the notification of the shared script right after logging in, then clicked on "Use a Script" and selected the shared script correctly.

- She clicked on “Notes” first, which was blank

- Next she clicked on “Instructions”, and commented that there were “lots of instructions”. She did not read those completely.

- She gave the example path as input, indicating that example placeholder text is helpful.

- She correctly changed number of processors as specified in the briefing.

- She saved the generated command into her notes and successfully edited the note.

- She found the sign out button easily.

- She logged in again, and clicked on history to use the same script again, with no confusions.

- She did not use the tooltips because she was familiar with the parameters, but she said the tooltips are cool.

- She also mentioned that it’s clear which field the warning text refers to since it’s slightly closer to the field above rather than below

- Overall she liked the interface and thought it was intuitive to use

- Any confusion she had she said was related to the fact that this was a test and not a real use case.

Notes from Computational Biologist 1

- He was familiar with the “intersectBED” script as specified in the briefing.

- He asked us if he already had an account with BioMate.

- He seemed a bit confused about what to put in “Alias” but figured out himself, and entered the same thing for Alias and User-friendly name

- He asked whether he can copy and paste within the command structure box.

- He clicked on “more info”, indicating that the more info button is sufficiently visible

- He copied and pasted the “input file” inside the table of the parameters, showing how the parameters table can be used for quickly updating parameters

- He did not use “Caveats” field, instead wrote warnings in the general instructions field

- At first he did not see the feedback from clicking "Save", but noticed it after saving a couple of times. He would like more visible feedback.

- The behavior of “Save As” was not what he expected. He clicked on “Save As” when he created a new script. (We expected the users to click on Save or Save and Share first.)

- Save As seems to be buggy. When the user clicked “Save As” before “Save”, sometimes none of the parameters were saved, and sometimes certain parameters or static text chunks were duplicated in strange places.

- He never used the “Use a Script” icon on the top navigation bar. He went to homepage each time and then clicked on "Use a Script"

- Did not notice that the label of a script on the Create/Edit page was editable.

- Asked, “is the only way to share a script through the Create/Edit page?” He might want to share his scripts from a list.

- He never made use of the warnings or tooltips for each parameter. He said these features seemed useful when we showed them to him, but it was not obvious from the interface what they were used for.

Usability Issues

Issue |

Rating |

Solution |

Instructions in the "Use a Script" page may or may not be informative, depending on how much effort the computational biologist put in when creating the script for sharing. |

minor |

Encourage computational biologists to write good instructions by adding placeholder text such as “Write good instructions so users will know how to use your script” |

The “Load Parameters” popup is blank and not informative before the user has saved parameter values for a given script. |

major |

The "Load Parameters" button should not even be visible until the user saves parameters. |

Tooltips in the "Use a Script" page sometimes overflow and are generally unhelpful. |

major |

Programmers should be given guidance when creating tooltips (e.g., character limit) such that tooltips do not overflow. |

It’s not obvious that “Use a Script” really just means “generate the command to run a script in the terminal”. |

minor |

Tooltip or instructions for the “Use a Script” page should clarify the purpose of the page. |

One user clicked “Save As” rather than “Save” when creating a script because he did not expect the script to initially have a name. It seems that our decision to force users to name the script first is not externally consistent. Most applications (e.g., Microsoft Word) only require the user to specify a name the first time the user hits “Save”. |

major |

Do not force the user to name the script until they hit “Save” or “Save As” for the first time |

Feedback from the “Save” button (e.g., "Saved at <timestamp>") is not visible enough in the "Create/Edit a Script" page. |

major |

Move the feedback to a more visible location |

It would be nice to be able to share scripts without going to the “Create/Edit a Script” page. |

minor |

Add functionality for sharing scripts from the home page |

The difference between “Caveats” and “Instructions” was not obvious to the user. |

minor |

Change the name of “Caveats” or change the placeholder text to make it clear what the difference is. Or perhaps get rid of Caveats all together. |

The purpose of “Warnings” and “Tooltip” were not obvious to the user. |

minor |

Show a picture so users can see how these would look in the interface |

For efficiency, it would be useful to be able to copy parameters. |

minor |

Add the ability to copy parameters from the table or from the draggable chunks. |

“Alias” and “user friendly name” seem to be redundant. |

minor |

Combine these fields into one field called “Name” |

Icons on the navigation bar are not obvious. |

minor |

Make the icons bigger and more visible. |

Reflection

We found the spiral design process to be quite useful. In particular, the prototyping and user testing helped to improve our final design a lot. During paper prototyping, we did a couple of iterations and it was very easy to test the different design alternatives we had. We could incorporate suggestions from the users into our designs on the fly which was pretty useful. We felt more committed to our design once we built our computer prototype since it required a substantial amount of work to implement. But we did make revisions in our design based on the heuristic evaluations we received from our classmates.

Sometimes prototypes can oversimplify tasks and important implementation issues can be overlooked. For example, with the paper prototype we did not need to care about how the backend of the application was going to work, how we were going to save the information about users and scripts, how scripts would actually be shared etc. However, it took a substantial amount of work to implement the functionality for the final implementation.

If we were to do this project again, we would test the script sharing functionality more. We would prototype two alternatives - in app sharing vs. sharing via email (this is implemented in our current application) to see which one makes more sense for the target users. We might also like to test whether users would prefer their saved parameters to be associated with an historical run of the script rather than named saved parameters which need to be explicitly loaded. Finally, if we had more time, we would have liked to prototype different alternatives to all of the different text fields in the programmer interface (caveats, instructions, warnings, and tooltips).

And last but not the least, from the final user testing, we actually discovered how our assumptions about the behavior of “Save” and “Save As” differed from what the users expected. Our assumption was not consistent with the typical behavior of Save As in commonly used applications such as Microsoft Word. We should have been more careful about making our design consistent with users’ expectations.