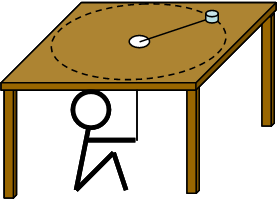

A small object with a mass of 0.250 kg has been attached to a massless string, and is moving in a circle on a perfectly level frictionless tabletop. The string passes through a hole in the center of the table, and is held by a person. Suppose that initially the mass is rotating with an angular speed of 15.0 rad/s around a circle of radius 0.400 m. The person then pulls the string in such a way as to reduce the radius of the circle at a constant rate. The person stops reducing the radius when the object is making a circle of radius 0.200 m. How much work did the person do in the course of reducing the radius of the circle?

Solution: We will approach the problem in two ways. First, we will use the work-energy theorem to obtain the answer in a straightforward manner. We will then compare our answer to that obtained using the (considerably more complicated) method of computing the integral of the force times displacement along the path.

Method 1

System: The object as a point particle undergoing pure rotation, acted upon by external forces from the string (tension), the earth (gravity) and the table (normal force).

Model: [1-D Angular Momentum and Angular Impulse] plus the [Work-Energy Theorem].

Approach: Gravity and the normal force are perpendicular to the motion of the object and so do no work. The only force capable of performing work on the object is the tension, which is equal to the force from the person pulling on the string. Thus, the work done by tension will equal the work done by the person. This work can be computed by finding the change in kinetic energy of the object, according to the Law of Change for our model:

\begin

[ W = \Delta K]\end

Because the object can be considered to be moving in pure rotation about the center of the circle, we can compute its kinetic energy using the rotational formula:

\begin

[ K = K_

= \frac

I\omega^

]\end

For a point particle,

\begin

[ I = mr^

]\end

and so:

\begin

[ W = \frac

m\left(r_

^

\omega_

^

- r_

Unknown macro: {i}^

\omega_

^

\right)]\end

Note that we have assumed the mass is constant, but we cannot assume the angular speed is constant.

We already have the initial and final radius of the motion, but we do not yet have the angular speed. To find it, we consider the torque on the system. We choose the natural location for the axis by locating it at the center of the circle.

With this choice, we can see that there is zero net torque on the system, since the moment arm for the tension is zero. With the net torque equal to zero, we are in the special case of constant angular momentum, so:

\begin

[ I_

\omega_

= I_

\omega_

]\end

By using the formula for the moment of inertia of a point particle, we can show:

\begin

[ \omega_

= \omega_

\left(\frac{r_{i}}{r_{f}}\right)^

]\end

Substituting into the work-energy theorem then gives:

\begin

[ W = \frac

mr_

^

\omega_

^

\left(\frac{r_

^{2}}{r_

^{2}} - 1\right) =\mbox

]\end

Method 2

System: The object as a point particle undergoing pure rotation, acted upon by external forces from the string (tension), the earth (gravity) and the table (normal force).

Model: Point Particle Dynamics, [1-D Angular Momentum and Angular Impulse] plus the definition of work.

Approach: To move the object radially inward at constant speed, the tension force must simply provide the centripetal force.

No additional radial acceleration is needed, since the change in radius is at a constant rate.

We therefore have:

\begin

[ T = m\omega^

r ] \end

Since, as discussed in Method 1 above, the only force that does work is the tension, we can now use the definition of work:

\begin

[ W = \int_{r_{i}}^{r_{f}} \vec

\cdot d\vec

= - \int_{r_{i}}{r_{f}} m\omega

r\:dr]\end

Note that the tension force points radially inward so that the dot product gives a negative sign.

Before we can evaluate this integral, we must determine the dependence of ω on r. As in Method 1, we make use of the fact that (if we choose the center of the circle for the axis of rotation) the angular momentum of the object is constant. Thus:

\begin

[ I(r)\omega(r) = I_

\omega_

]\end

Or, by using the formula for the moment of inertia of a point particle:

\begin

[ \omega(r) = \omega_

\left(\frac{r_{i}}

\right)^

]\end

Inserting this formula into our expression for work gives:

\begin

[ W = -\int_{r_{i}}^{r_{f}} m\omega_

^

r_

^

r^{-3} \:dr = \frac

mr_

^

\omega_

^

\left(\frac{r_

^{2}}{r_

^{2}} - 1\right) ]\end

The same expression found using Method 1.