Table of Contents

Problem Statement

- In the chaotic emergency care environment staff members must make snap judgement about patient treatment. Doctors, nurses and other members of the hospital staff need an efficient way to keep track of patients coming into and going out of the medical care units. They also need to keep track of patient medical status, interventions performed, and medications administered. To perform their role as caretakers effectively, they must also note which members of the staff are responsible for which patients. A common medium for information management in this fast-paced environment is a simple marker and white board, which doctors and nurses share to keep track of this large and complex network of information.

- While the whiteboard does score high on the efficiency and learnability scale, it is a dismally unsafe and prone to all kinds of error including lapses, mistakes, poor form, smudging, and other forms of human error. For an institution whose goal it is to provide care, the dismal safety score of the whiteboard merits a revamped user interface design.

- Several institutions employ existing medical information management platforms, but clinical staff often describe these tools as "cumbersome", "inefficient" and "annoying", and often prefer to use the white boards instead.

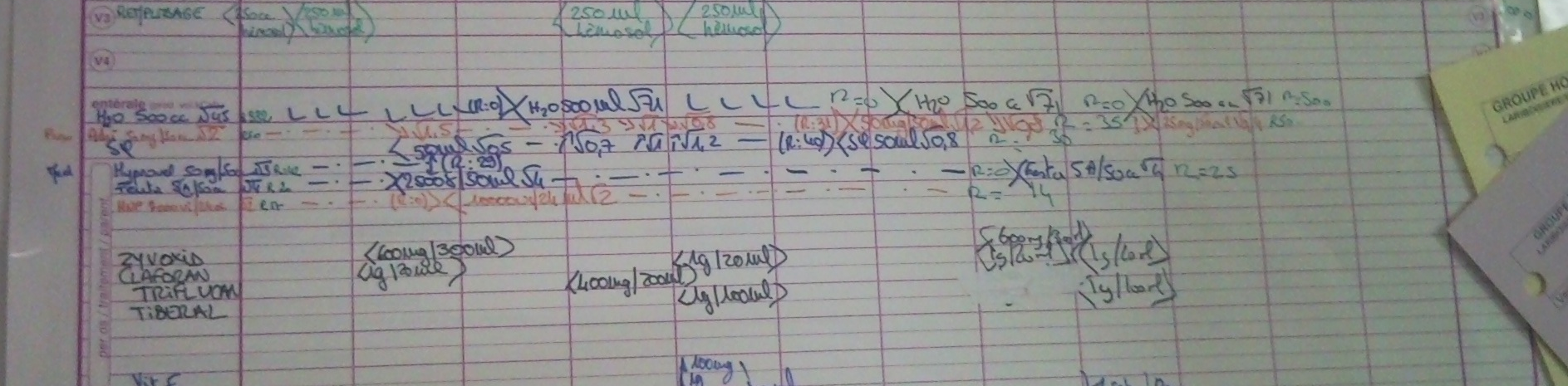

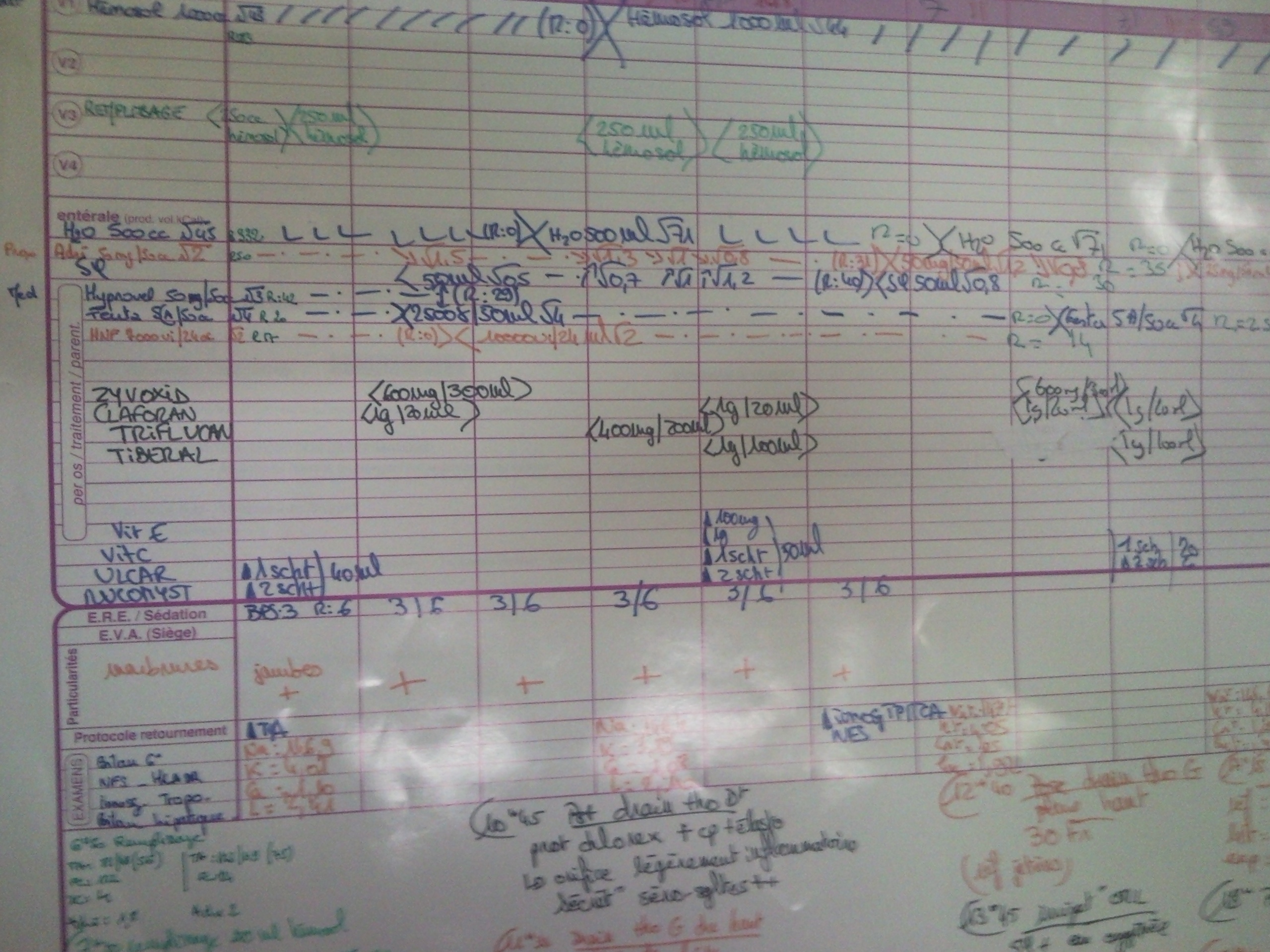

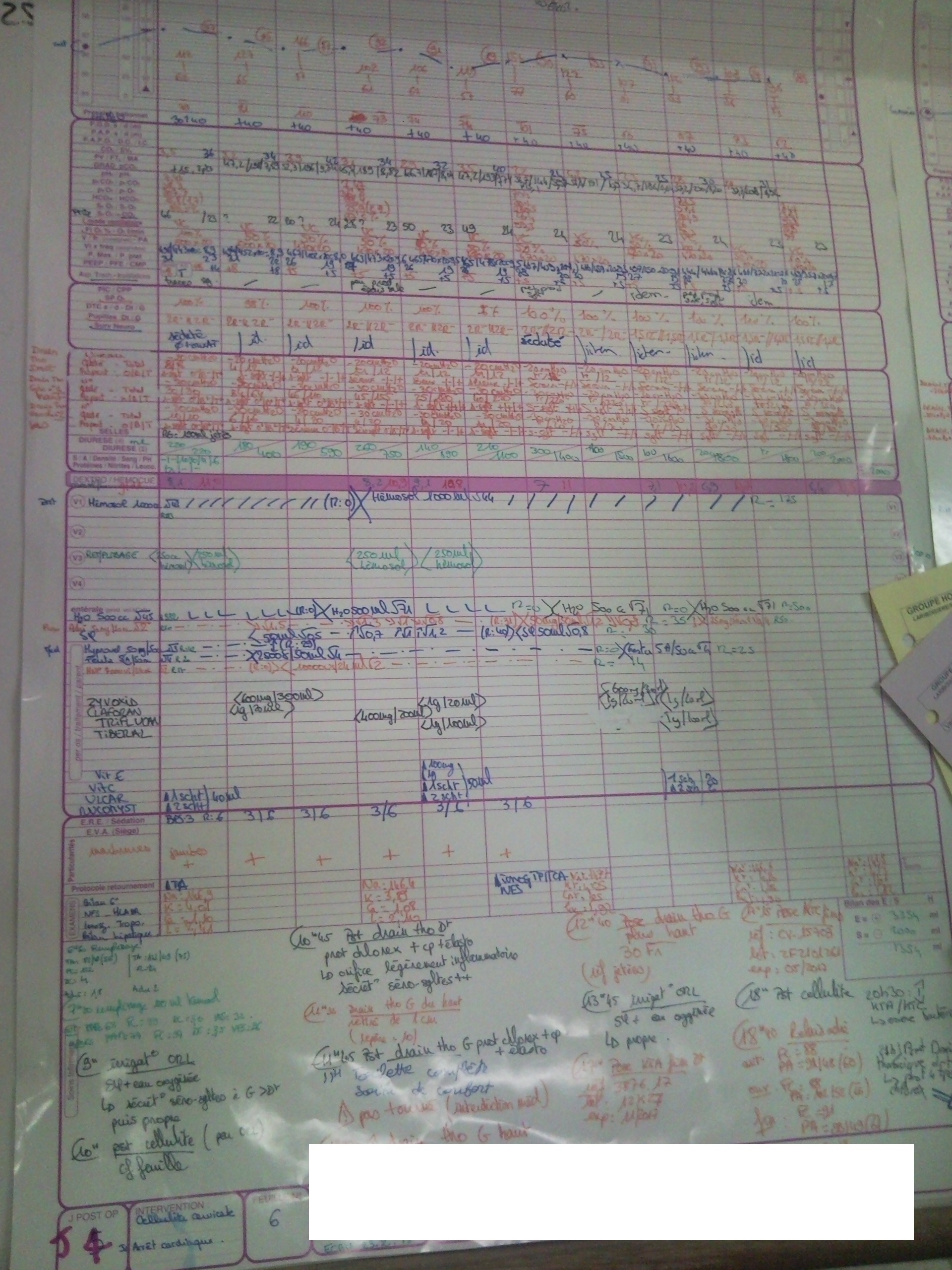

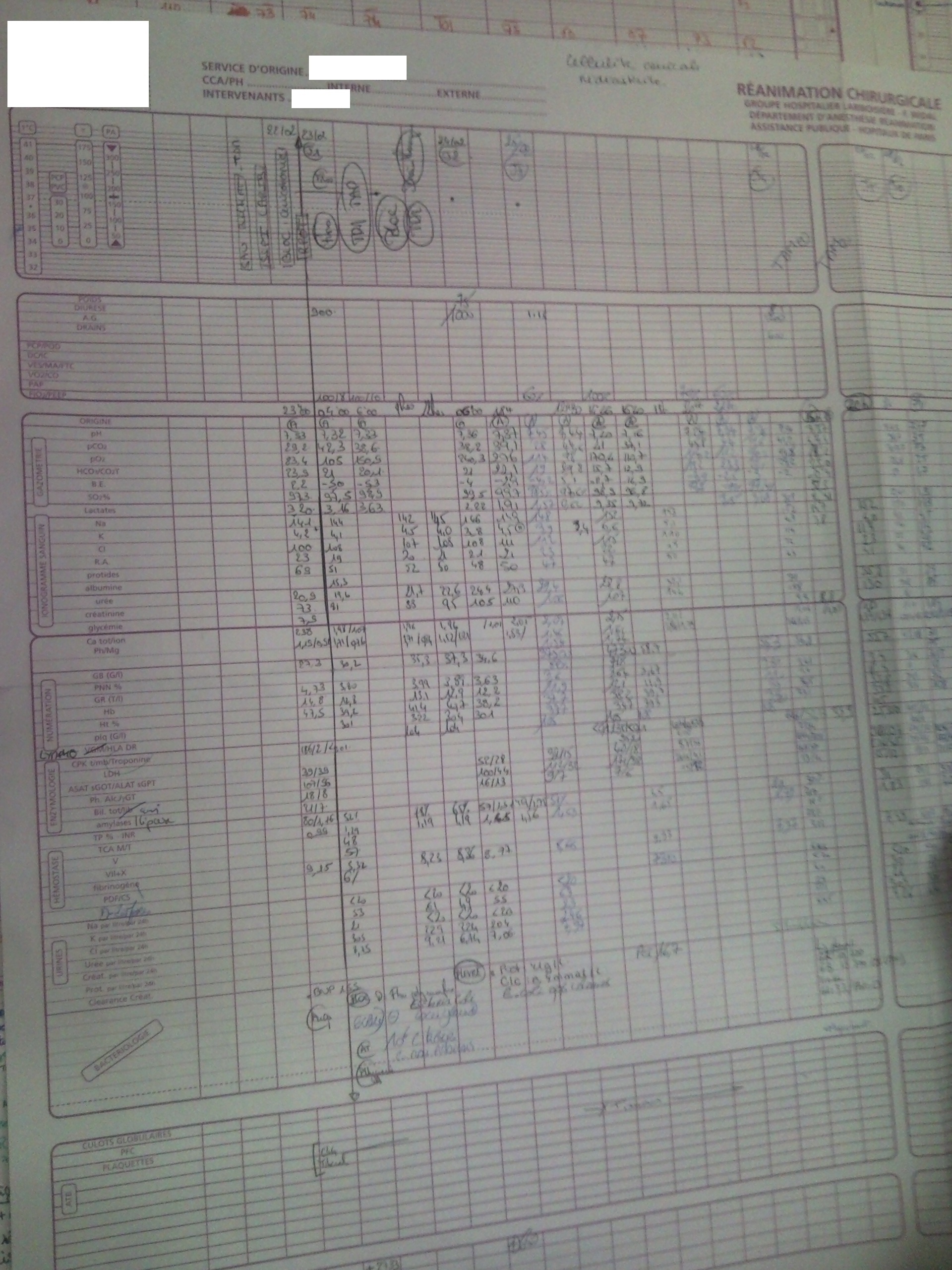

Example of the current platform

Figure 1:

User Analysis

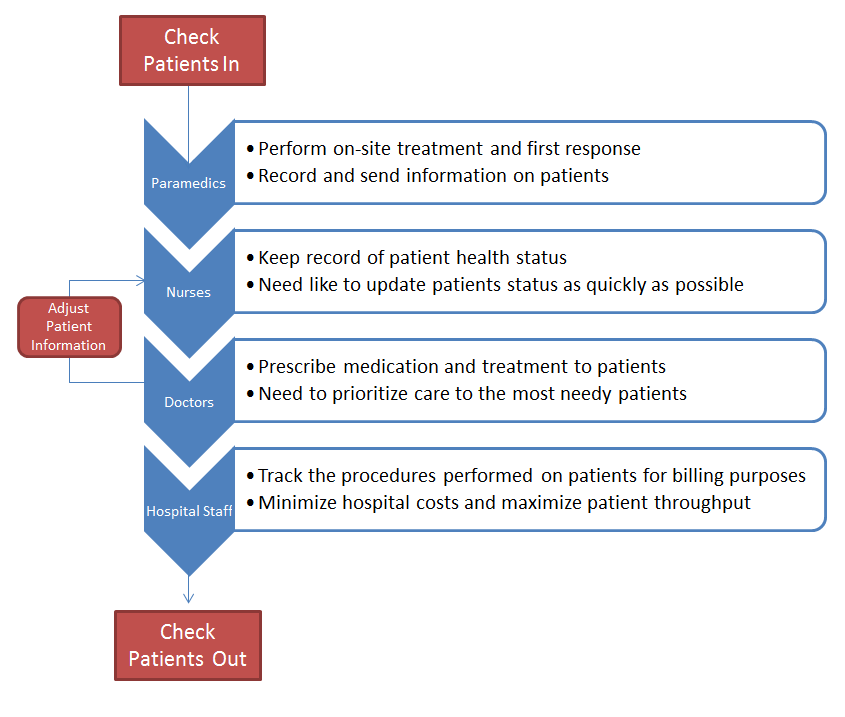

Flowchart

Flowchart 1:

Target Users Classes and Their Goals

Here we present the users classes in order of contact with the patients, as well as their treatment goals.

1. Paramedics

- Goals

- Perform on-site treatment and first response

- Collect and record patient information as they are being transported to the hospital

- Inform the hospital of incoming patients and provide information on health condition

- Needs

- Record and send information on patients to the hospital as early as possible to ensure that the caregivers are ready to receive and provide immediate treatment

- Obstacles

- No efficient way to communicate or send information collected in the ambulance to the hospital.

- Must frequently repeat verbal descriptions of patient status and recount patient information to hospital staff

2. Nurses:

- Goals

- Help patients transition from the ambulance to the care-units

- Keep record of patient health status

- Assess situation and collect further patient information to prepare patients for doctors

- Administer prescribed meditations

- Needs

- Need to manage patient information cleanly, and safely without negatively impacting their operational efficiently

- Need like to update patients status as quickly as possible

- Obstacles

- Existing platform is highly error-prone, and can be difficult to discern

- Existing platform is cumbersome and information is not easily transmitted. This can lead to a latency issue where information is not updated frequently enough.

3. Doctors:

- Goals

- Prescribe medication and treatment to patients

- Provide more detailed (or accurate) diagnoses of patients' conditions

- Provide oversight of operations

- Tackle specialized medical problems

- Needs

- Need to prioritize care to the most needy patients

- Need to be able to easily access patient medical data

- Obstacles

- Very little time to learn new or challenging user interface designs.

4. Other hospital staff:

- Goals

- Track the procedures performed on patients for billing purposes

- Contact family members

- Needs

- Minimize hospital costs and maximize patient throughput

- Receive updates about patient status as quickly as possible

- Obstacles

- Have difficulty understanding "Jargon" of the clinical staff, and layout of the information on the white boards

- Are not informed of updates in status without rechecking the board, which is itself prone to latency issues.

5. Patients

Patients in the ICU are critical condition. Therefore we don't consider patients as forming a user class.

Task Analysis

There are essentially two types of tasks that users engage in as part of the patient information management process. Here we will describe the two tasks with respect to the environment in which they are performed.

Common Constraints across Tasks

- What is the environment like?

- The environment is loud, crowded, and hectic. Patients, those accompanying the patients, doctors, nurses, paramedics, and other hospital staff are all in the area. Discussions between the patients, families, doctors, nurses, etc. create a noisy environment, and constant movement of hospital staff (including nurses and doctors) makes the environment a bustling one for both check in and check out.

- What are the time or resource constraints?

- There are both time and resource constraints. Saving minutes could save lives, and so nurses, doctors, and other hospital staff try to make all interactions efficient.

- Most hospital ICUs seem to be understaffed. There are often fewer doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff than would be ideal, and so those professionals must split their time between the patients they are seeing.

- Some hospitals have the added constraint of limited space. Many ICUs have a relatively low limit on the number of patients they can hold (which could be a function of the point mentioned above: staffing).

Task 1: Checking Patients In and Out

- Why is the task being done?

- Hospitals must keep detailed records of the patients for whom they are caring, and this record-keeping process starts with the patient check-in. The patient check-in process allows the hospital to know when patients have begun care, and allows the hospitals to collect one-time information from the patients (insurance information, contact information, etc.).

- The check-out procedure involves the consolidation of collected medical information on a patient into a medical file.

- Where is the task performed?

- Patients are checked into the ICU, usually by the paramedics delivering the patient in coordination with a nurse or other hospital staff. Occasionally, when a patient's condition is less critical, check-in happens at a registration desk where further information is also collected.

- The checkout procedure is less hectic than the check-in, with information being moved from the whiteboard to a paper backup file.

- Who else is involved in the task?

- As mentioned above, there are several classes of people involved in the admission and discharge process. In fact, each of our user classes described in the sections above plays a fairly distinct role in the task of checking patients in and out. Doctors are likely less involved in this particular task, but nurses, paramedics, and other hospital staff certainly each play a large role in checking patients in. While nurses and hospital staff handle checking patients out.

- What does the user need to know or have before doing the task?

- Users need to know where the patient is located, and what the status of the patient is. If the patient is conscious and able to answer questions, then this task can be reduced to a simple interview of the patient being checked in with medical details added. However, in the relatively common case of a patient who is unable to answer for him- or herself, the users must know about the patient's medical history as best they can, the current condition of the patient, and any other information that might help with diagnosis, triage, and treatment of the patient.

- How often is the task performed?

- The task is performed on every patient entering the ICU. For most hospitals, the rate of patients entering fluctuates greatly throughout the day, and our initial research and interviews have shown that it can range from 3-60 patients per hour depending on the hospital, and location.

- How is the task learned?

- The task is usually learned through training and hands-on observation. New emergency nurses are often trained in a "live" ICU, while doctors spend years of internships and residencies during which they also develop the necessary clerical techniques. Other hospital staff also receive training on patient check-in processes.

- What can go wrong?

- Our research, observations, and interviews have shown that several things can go wrong during patient check-in. On occasion, some patients might "slip through the cracks" and not be checked in at all; this is a large problem when it occurs. Patients may also be checked-in with the wrong information accompanying their records, which can be especially problematic when the false information includes an incorrect medical history or medical status.

Task 2: Adjusting Patient Information

- Why is the task being done?

- The patients' information is being updated so that the hospital always has an accurate record of the patients' status. The status recorded is used for all sorts of treatment and logistics, so it is important that it stays up-to-date. In addition, patient condition changes relatively frequently, and the hospital staff must keep track of treatment administered.

- Where is the task performed?

- This task, like the one above, is performed primarily in the ICU in question. Specifically, the task is most often performed alongside the patient, usually at or near his or her bed. On occasion, the patient's information might be adjusted from a remote room.

- Who else is involved in the task?

- Generally, doctors are more involved in updating a patient's information than they are in checking the patients in, and by the time that patients need their information updated, paramedics are usually out of the picture. So, doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff are the main user classes involved in this task.

- What does the user need to know or have before doing the task?

- The users updating the patients' information must know the patient's identity, or at least his or her identification in the hospital's records, and what information the user is updating.

- How often is the task performed?

- Again, through our observations, interviews, and research, we've found that patient information can be updated as frequently as 12-30 times per hour per patient! Averages are lower, though: it is much more common for a patient's file to be updated hourly.

- How is the task learned?

- Similarly to the checking-in task, the process of updating a patient's records is learned via training and hands-on application of skills.

- What can go wrong?

- Everything that could have gone wrong during patient check-in is also a potential breaking point in this information-updating task. There is one more very significant and realistic threat of error introduced in this task, however: mistaken patient identification. It is very possible that a member of the hospital staff mistakenly updates the wrong patient's information.

Interviews

Interview 1: Doctor X

Dr. X is a young radiologist who often works in ICU. As he has very good IT skills (MIT CS level), we thought it would be a great idea to have his feedback on the current platform used for information management. He described his work in the ICU saying "Patients in ICU can stay for a few hours up to a few weeks. The goal of the hospital employees is basically first to keep patients alive, and second, if they succeed, to treat them." Dr X. then explained how the patient's data are handled by the hospital employees. "The medical information on each patient is currently stored in two different places: a file folder (paper) containing the main general information on the patient, such as the patient's medical history, physicians' observations, his age, etc. A whiteboard on which it is indicated which drugs the patient has received in the ICU, and at what time he/she received it. The whiteboard also contains key information on the patient that everybody should know, typically allergies and main diagnosis.

We asked him who used this information. He replied physicians, nurses as well as unlicensed assistive personnel need access to them. For example when unlicensed assistive personnel give a meal to a patient, they should know if the latter is allergic to it.We then inquired what key goals and needs he has which are not addressed by the current solution (file folder + whiteboard)

Key points

- Patients with intricate medical records are difficult to handle as the whiteboard only has enough space for a few major pieces of medical information. It's primary purpose now is to keep track of drug administration.

- The whiteboard makes it impossible to collect data for medical research.

- Physical papers can be lost/altered, and are inconvenient to move (in case the patient needs to be moved).

- Many measurements are done on the patient and displayed in real-time but then need to be manually written on the whiteboard, and never make it to the patient's file folder.

- Since information on the whiteboard aren't recorded in the patient's file folder, if one day another physician needs to give a drug to the patient that he had received during a previous ICU period, the physician will not know how the patient had reacted to it.

- When something's wrong and strange with the patient, it can be helpful to browse the detailed history (or for research purposes), but globally it doesn't happen often: 2-3 days after it's been measured it most likely won't ever be needed again.

Interview 2: Doctor Y

Dr Y. is a young ICU physician. As the ICU is a broad topic and in our interview we focused on how patient's information is handled. He described 5 different types of information containers (everything is contained on paper except the first one):

- Administrative and general demographic information: everything non-medical, e.g. age/sex/address/...

- Basic medical information: upon the patient's arrival to the ICU, a physician interviews the patient (provided that the patient is able to talk) and writes a medical summary of 1 or 2 pages containing anything that could be of interest to treat the patient. This synopsis follows a conventional format. It will be kept within the hospital, even after the patient has left.

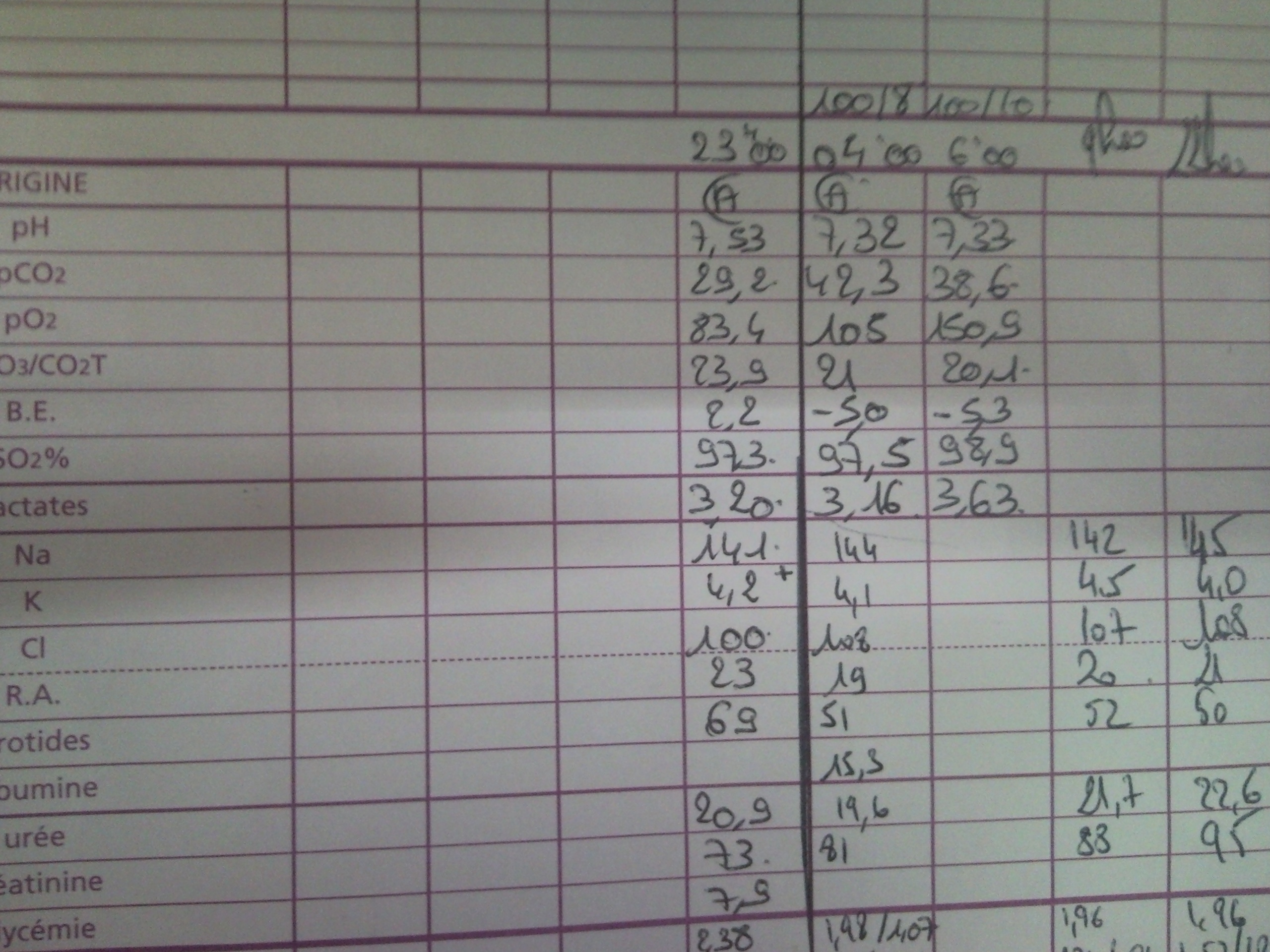

- Nurses notes: precise technical information such as drugs given (quantity/time) as well as key measurements on the patient such as blood pressure or ECG.

- Nurse whiteboard: Another platform for recording data measurements (blood pressure/ECG/…), drugs, key events.

- Assistive personnel whiteboard: Summary of the previous examinations of the patient in addition to the other 4 sources of information. There are some computer applications designed for specific types of information such as medical images, but those applications aren't interconnected.

Key points

Dr Y. enumerated his most important needs for a medical information management system:

- Easy, rapid access to any information pertaining to the patient.

- Reliability of the information, e.g. not having the wrong, or incomplete data on a patient (this seems obvious but it does cost many lives annually).

- Having one information container instead of the myriads of information sources he currently has to deal with.

Interview 3: MIT paramedic

M. spent a year as an MIT paramedic, so she was responsible for patients from the time that 911 or Campus Police were called until the patient was officially transferred to a nurse at the hospital. She described the typical process for handling a patient and his/her information:

A paramedic dispatch begins with a one-line description of the case, sent over the radio from the 911 dispatch, such as "18 year-old male complaining of stomach ache in Next House." The paramedics respond to the dispatch with a priority number between 1 and 3 (1 being the most serious), which determines the level of urgency with which they travel in the ambulance. In practice, they would always respond with Priority 1, since without having seen the patient yet they can't be sure that there is not a life-threatening emergency. Once on the scene, the paramedics measure the vital statistics of the patient (BP, pulse, state of consciousness, etc.), make an on-site treatment is necessary, and then measure all the vital stats again. The stats and treatment are all recorded on paper carried by the paramedics.

At this point, the paramedics will either transport the patient to MIT Medical or a local hospital, or the patient can decline to be transported and sign a waiver releasing the paramedics from responsibility. Assuming the paramedics decide to take the patient to the hospital, they will then transport them, again with a Priority number of 1, 2, or 3 (having now seen the patient, they can actually decide on the priority rather than just always choosing Priority 1). The paramedics communicate with Central Medical Emergency Direction (CMED), which coordinates between hospitals and paramedic, and they provide CMED with their priority number and another one-line summary of the patient's condition over the radio.

At the hospital, the paramedics bring the patient and the notes they have recorded about times, statistics, and treatments to the primary triage nurse, and they once again give their one-line summary of the incident. This nurse has a mobile computer of some kind, and enters the information provided by the paramedics manually, if time allows. The paramedics then follow the patient to another room with another nurse, and they repeat their one-line description yet again to this nurse. At this point, they are no longer responsible for the patient's care.

Finally, the paramedics fill out a full report of the incident. At MIT, this is done on a computerized system, in which the notes taken on paper by the paramedics are entered manually into a form. This form contains all of the relevant times (when the ambulance left, arrived, treated the patient, etc.) and statistics of the patient and any treatment given, and it is signed by all the paramedics who responded to the call. This record is sent to the hospital, MIT, and the ambulance service (in this case, MIT paramedic).

Key points

M's primary concern with the way the patient information was handled was the many, many repetitions of a short, one-line summary of the incident, which they had to give to CMED and to nurse after nurse after nurse, which was often a waste of time. In addition, she felt that much of the nurses' time was wasted re-entering information already collected by the paramedics into the hospital's system.

M. mentioned that she knew of at least one paramedic using a voice recorder for extremely urgent calls, in which there was no time for written notes, but that this created privacy issues since the recordings contained sensitive patient information.

Takeaway Goals

- The platform of patient information must maintain the safety of information transfer in ICUs.

- The platform must also be highly efficient to accommodate common ICU situations.

- The platform must be quick-to-learn and robust to allow for easy use by the various user classes who could be using it.

- The platform's underlying model should be information dense, but should present only the pieces of data most relevant to each user group.

Appendix A: Images of the Existing Platform

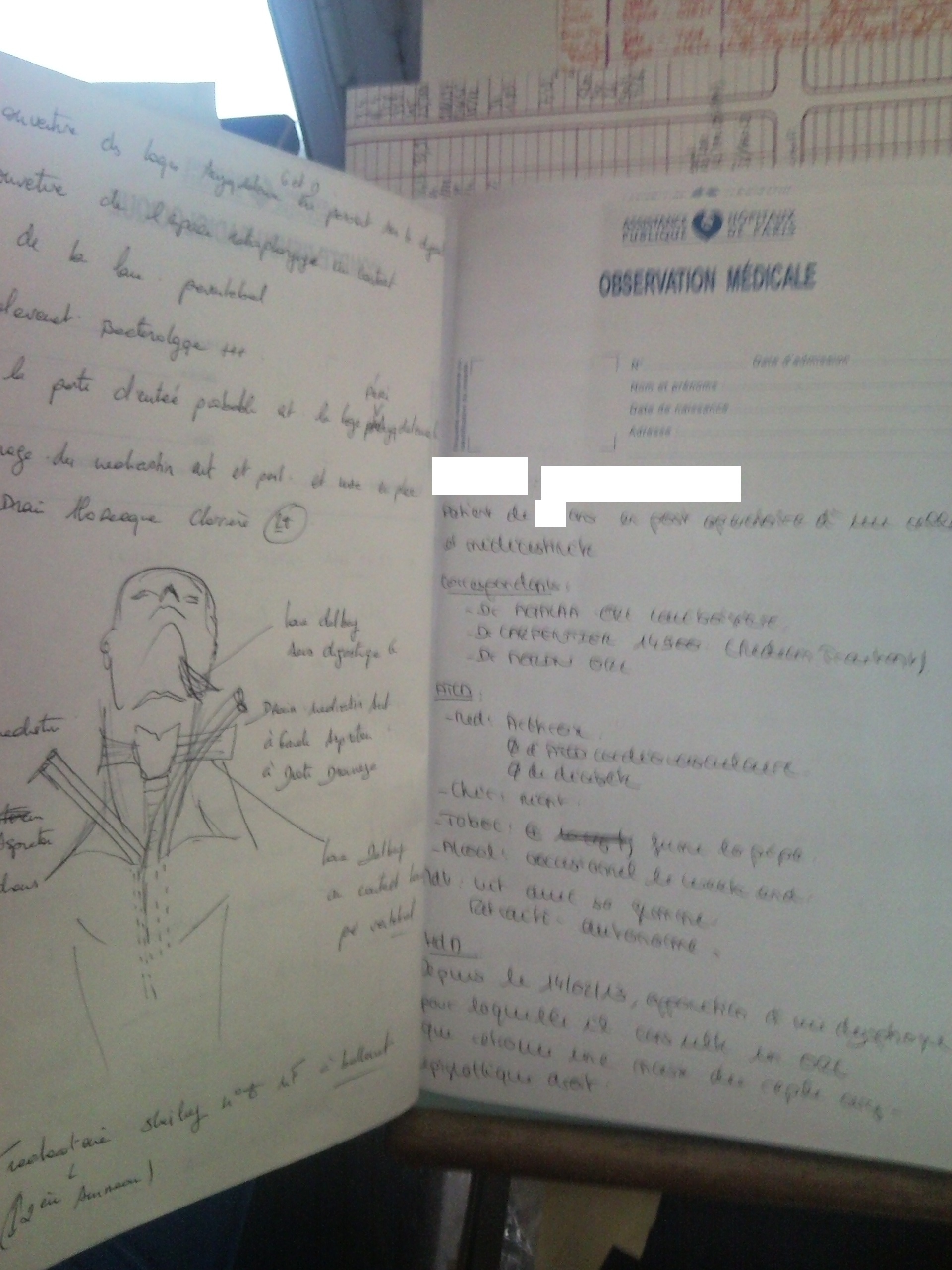

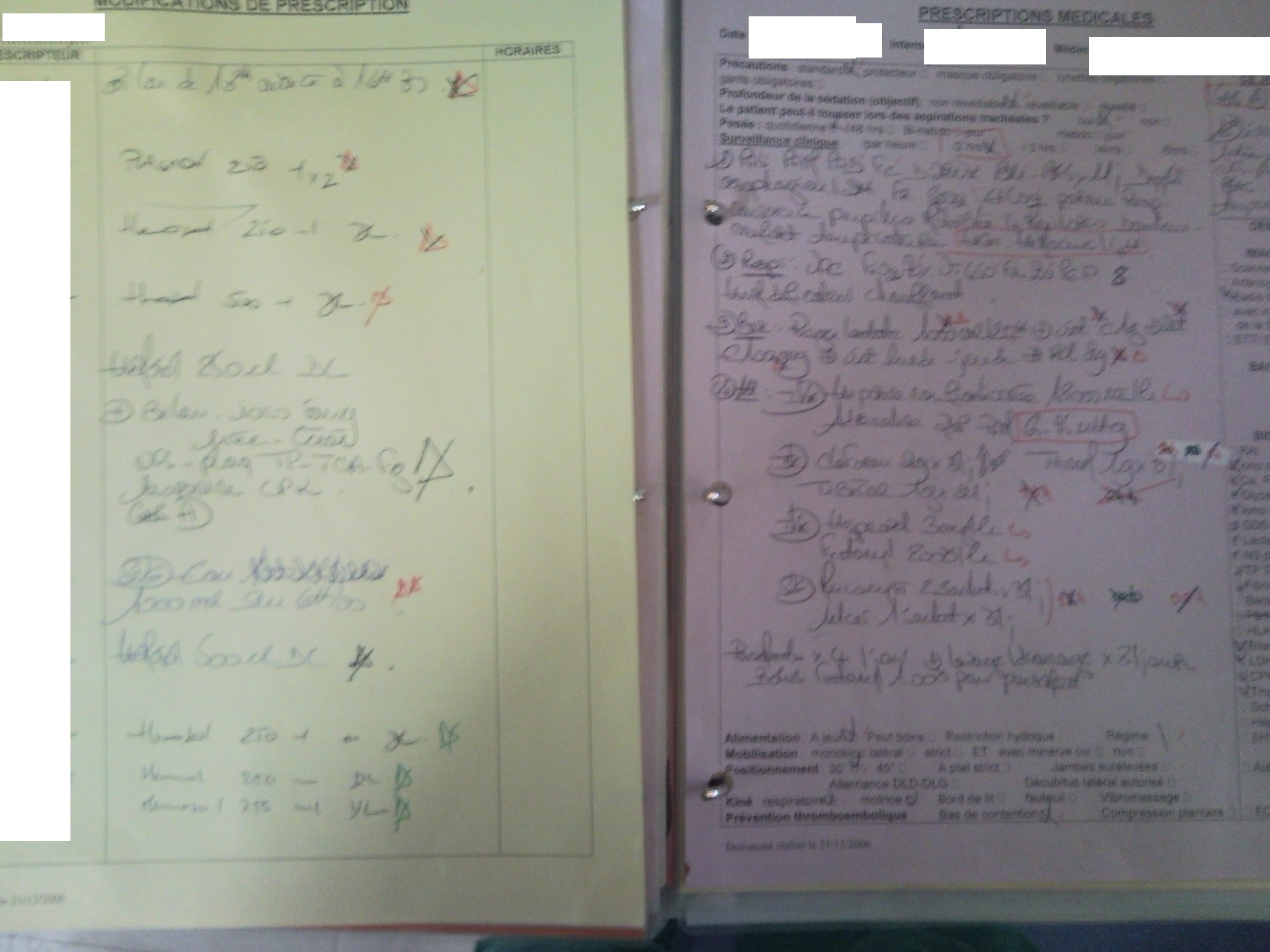

Medical Folder

Figure 2:

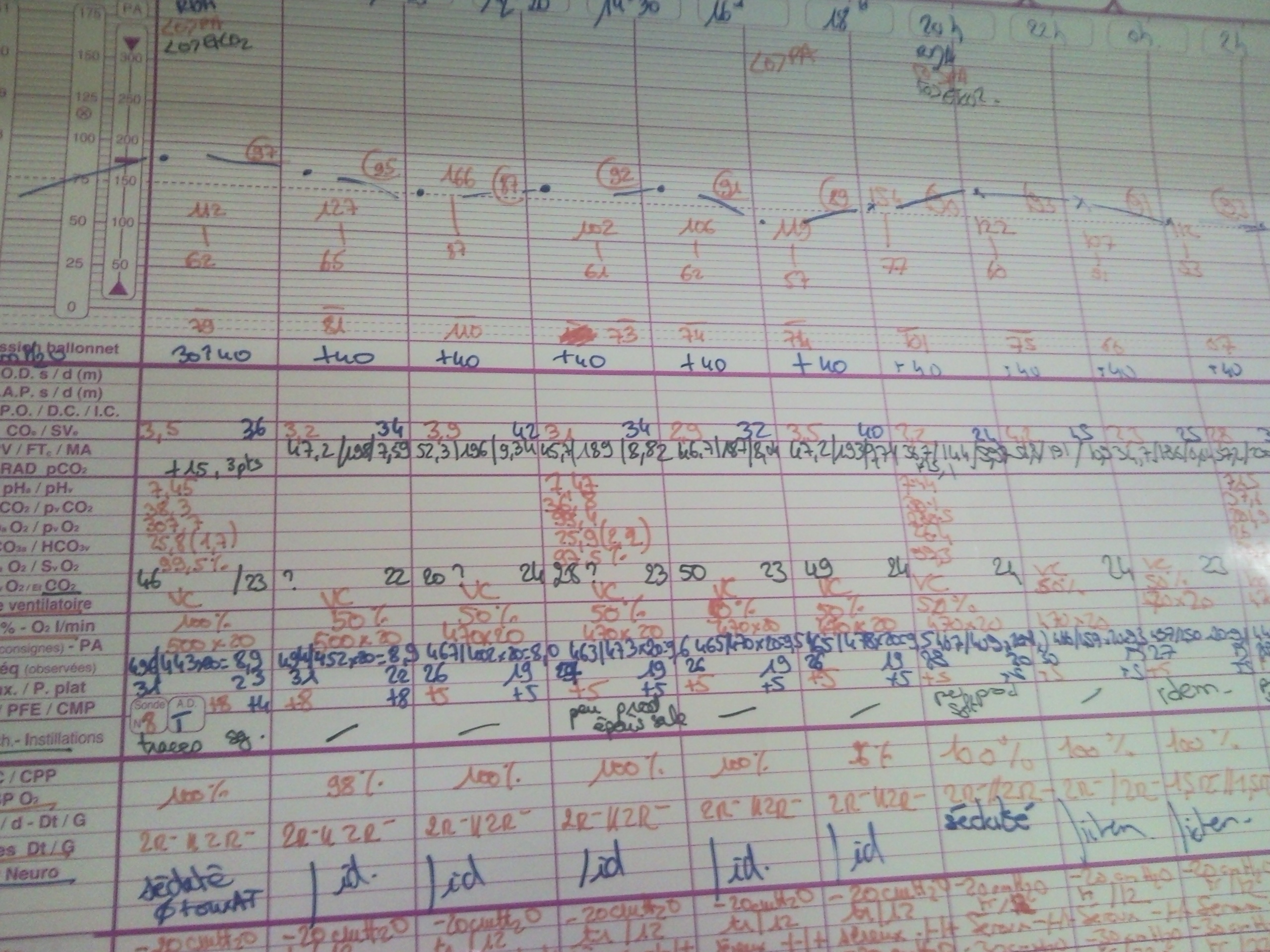

Nurse Whiteboard

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Figure 5:

Physician Prescription

Figure 6:

Physician Whiteboard

Figure 7:

Figure 8:

1 Comment

Unknown User (jks@mit.edu)

Overall: Great job with in-depth user interviews, and a user and task analysis centered around the shortcomings of using a whiteboard / paper notes for managing patient information.

Going forward: